Skills Addressed

- Reading with attention to meaning, not just “word calling”

- Purposeful reading (rereading) of text (to tell partner what you learned)

- Self-monitoring of comprehension (“What do I really understand?”)

- Recalling what was read while not looking at text

- Distinguishing more important from less important words, concepts

- Writing information in own words rather than copying from text

Prerequisites

- Understanding that reading is more than pronouncing the words

- Experience with thinking about the meaning while reading

- Willingness to talk to and listen to a partner

- Ability to express what one learned from a text orally (and in writing)

Steps Involved (See Detailed Step by Step Below)

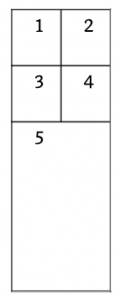

- Students work in pairs; each individual gets Key Word Notes form

- Everyone reads designated piece of text individually, silently

- Each student selects 3-4 words as memory aids, writes in Box 1

- Partners tell each other what words they selected and why

- Students repeat steps 2-4, completing all segments, using boxes 2, 3, 4

- Books closed, each student uses his/her Key Words to write summary in box 5

Related Learning Principals

- Choice enhances learning and contributes to positive attitudes.

- Comprehension is reinforced and enhanced by adequate processing time.

- Bursts of concentrated attention are better than continuous attention.

- Articulating what one has learned reinforces the learning.

- Learning is enhanced when students read, listen, speak, and write.

- Meaningful repetition cements learning.

Application

This strategy works across grade levels and content areas but is best in grades 3-12. Can gradually increase segments to read and numbers of words to select at each reading. To differentiate instruction, have students read different texts, matched to their reading levels. Have students use strategy independently when they are studying or doing research.

Step by Step

Before being successful with this strategy, students need experience identifying important details when they read informational text, and they need experience listening to and responding directly to a partner. When they are comfortable with these aspects of the process, here is how to proceed:

Have students prepare a page in their notebooks that looks like this image to the right.

Have students prepare a page in their notebooks that looks like this image to the right.- Divide the text students are about to read into four sections. Each section should be about 200–250 words long, which means it will probably include several paragraphs.

- Have students write the topic at the top of their papers and note the beginning and end of the first section.

- Organize students into pairs and give them the directions: Read the first section to yourself and identify three or four words that you think will help you remember the most important information in that section.You may choose any words you like as long as you think they will help you remember the information. Write the words you choose in Box 1. When you and your partner have each chosen your words, take turns explaining what words you chose and what information they will help you remember. You may keep your books open as you talk and may refer to the text if you wish. Limiting students to so few words keeps them from copying the text word for word. Also, because the task is to select words that will help them remember the information, they are more likely to think about the information as they read instead of reading quickly and inattentively.

- When students have finished discussing their word choices for the first section, tell the class the ending point for the second section and have them read, select key words, write them in Box 2, and talk in pairs about their choices.

- Repeat the process for the third and fourth sections of the text.

- When students have finished reading all four sections, have them put the book aside and individually write about what they learned in Box 5, using all of their selected key words.Here is an example of a reading selection about earthquakes and the beginning of a Key Word Notes page that one student created to help her remember what she read:

Feeling the ground move in an earthquake can be scary, but people are seldom hurt by the shaking. Instead, most injuries and deaths are caused by things that fall, break, or collapse when the earth moves. For example, windows may pop out of buildings and come crashing to the ground with great force. Brickwork in chimneys and on walls is easily weakened in a quake, and when the bricks pull away from one another and fall, they can injure people below. Large rocks on hillsides can also be dislodged in an earthquake and can tumble down onto houses, cars, and people without warning. Heavy t

ree limbs, too, may break off and fall, crushing property and injuring people. Bridges, roads, and railway tracks can also be twisted and cracked in an earthquake. For instance, in the 1989 San Francisco quake, some highway overpasses buckled so badly that they had to be torn down. The roadway on one bridge gave way completely, leaving a gaping hole in the bridge high above the water of San Francisco Bay. Tunnels can also be dangerous places during an earthquake. No matter how well built a tunnel is, the walls may crack or collapse if the earth around it is jolted enough.

Additional Suggestions

- At first, as students are learning the strategy, it’s best to have them read short sections and choose only three or four words. As they become more adept with the process, you may wish to increase the length of the sections and also the number of key words students will select.

- If students do not catch on to the process, model for them by reading the sections with them, selecting your own key words, and sharing with the class which words you chose and why. You may also want to model how to write a summary of the information using all of the words you chose.

- You may wish to vary the number of sections, depending on the way the text is structured. For example, students might read only three sections before using their key words to write a summary, or they may read more than four sections.

- Encourage students to use this strategy on their own as they engage in research for reports or as they study content-area texts. They can pair up with a friend or they can simply pause periodically when they read, select words to help them remember the information, and summarize their learning in writing at the end.

Nessel, Denise D.; Graham, Joyce M.. Thinking Strategies for Student Achievement (p. 110). SAGE Publications. Kindle Edition.